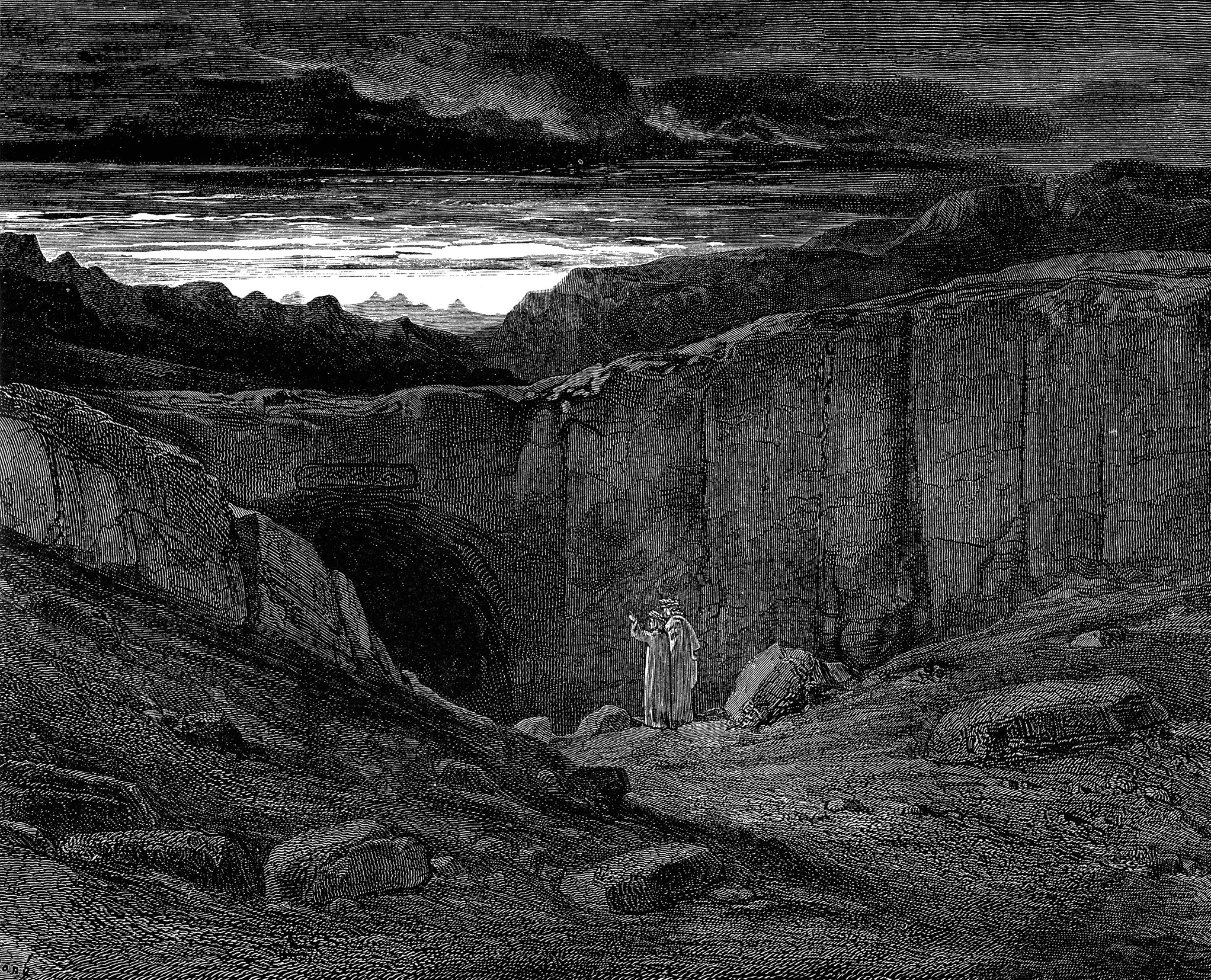

Enter the void

Later, the Greek philosophers Leucippus and Democritus took a different view, envisioning a gulf through which danced particles of various geometries and sizes. Aristotle later wrote of this theory, “The many move in the void, and by coming together, they produce coming-to-be, while by separating they produce passing-away.” Atoms were thought to be indivisible and indestructible because they contained no empty space inside them.

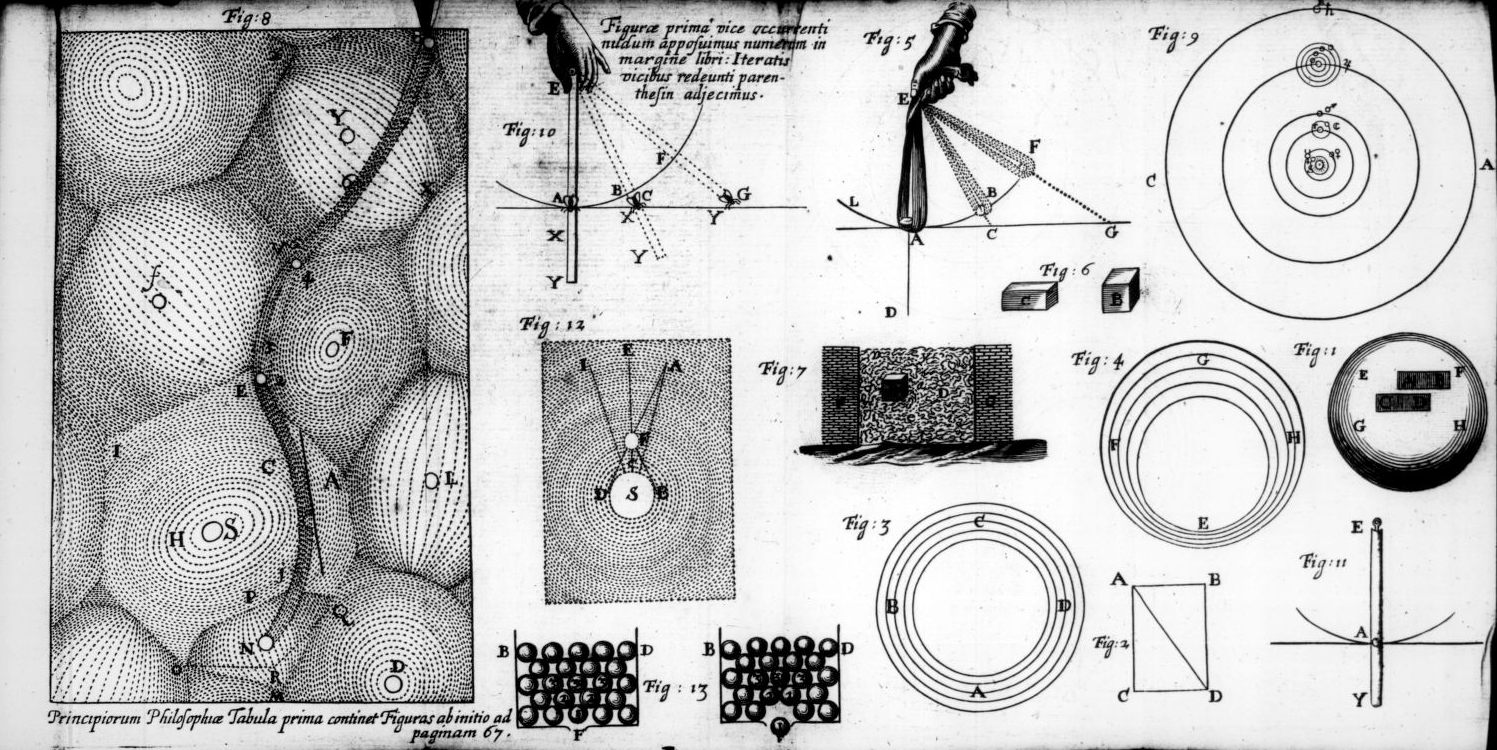

Aristotle also added a new type of substance, which he called the aether, to explain how solid bodies like stars and planets moved through space. Much later, René Descartes conceived of the aether as a physical substance traversed by vast and violent vortices.

1. First, he conclusively demonstrated that atoms of finite size were real by mathematically describing the movement of particles suspended in water.

2. Second, his newly devised theory of special relativity showed that light could in fact travel through empty space without any need for an infinite aether to transport it.

Let’s look at both of these carefully, starting with atoms. If atoms have a bottom limit to their size, then — conceivably — the three-dimensional space they occupy, however small, is made of something diametrically different from the empty space surrounding it.

But things get tricky when it comes to size, of course. Physicists in the 20th and 21st centuries made the crucial discoveries that atoms were actually made of protons, neutrons, and electrons.

Protons and neutrons were thought to be indivisible for a while, until physicists began shooting subluminal electrons at them in underground, mile-long particle accelerators. This causes atoms to explode and allows physicists to sort through the sub-atomic debris. Because of this work, we now know that protons and neutrons are actually Kinder eggs full of quarks.

That’s okay…maybe quarks are the smallest things that exist.

Unfortunately, some very sharp physicists — armed with sophisticated mathematics — demonstrated that quarks might actually be made of tiny vibrating strings.

Could there be anything smaller than a string? Since, in order to talk about strings, you must first invoke the existence of eleven different dimensions, we’ll just say it’s complicated. But you can still zoom in further. If you shrink down to the mathematically smallest measurable scale, called the Planck length, you might find yourself surrounded by miniature black holes. Don’t bother asking if there might be anything smaller than the black holes. You won’t like the answer.

We haven’t yet exhausted our supply of elementary particles, but the trend is much the same elsewhere. Electrons seem to be indivisible, unless you channel them through a wire held very close to a conductive metal at temperatures that hover just above absolute zero degrees Kelvin. This kickstarts a process called quantum tunneling, in which electrons jump from the metal to the wire. The close proximity of these electrons, the cold temperature, and the repellant force of their negative charges causes the electrons to split into particles called spinons and holons. Alternatively, if you fire photons of a particular wavelength at an electron under the right circumstances, you can get it to split into a spinon and orbiton.

We could discuss other fundamental particles that are seemingly indivisible, such as neutrinos. We could even follow this line of thinking all down into an infinitely recursive bottomless hole, as envisioned by Carl Sagan:

“There is an idea — strange, haunting, evocative — one of the most exquisite conjectures in science and religion. It is entirely undemonstrated; it may never be proved. But it stirs the blood. There are, we are told, an infinite hierarchy of universes, so that an elementary particle, such as an electron, in our universe would, if penetrated, reveal itself to be an entire closed universe. Within it, organized into the local equivalent of galaxies and smaller structures, are an immense number of other, much tinier elementary particles, which are themselves universes at the next level, and so on forever.”

The answers we get by zooming in illustrate something important. Thinking of particles as small points in space is a fundamental misinterpretation of how our universe is held together. Reality is far stranger and more fascinating.

We know that what we think of as an atom is mostly empty space, and both relativity and quantum mechanics have something to say about what that space is made of.

What if we took a close look at that emptiness to see if it contains something or nothing?

In the smallest atom, hydrogen, a single proton is distantly orbited by a lone electron roughly 5.3 X 10-11 m away. If a proton ballooned to the size of your head, its nearest electric partner would reside at a distance of about three miles. That’s plenty of room to go poking around for nothing.

Except, in quantum physics, electrons never occupy a single space at a given time. Rather, they are in a superposition of every possible location around the atom’s nucleus, until you look at them, and they furtively pick a single position. So the empty space within atoms is not really empty. Instead, it’s a vague expanse of potentiality with fuzzy borders that extend to the edge of the universe, if such a thing exists.

You could try freezing atoms!

If you cooled atoms all the way down to absolute 0 degrees Kelvin, that should get the electrons to stop moving, allowing you to inspect the nothingness between them. But here, quantum mechanics throws another curve ball.

According to Werner Heisenberg, and a theory he developed called the uncertainty principle, the more you know about a particle’s position, the less you know about its velocity. This is not due to the limitations of scientific instruments, but instead thought to be an inherent property of matter and energy.

If you could completely freeze an atom, you could determine exactly where its electrons, protons, and neutrons were located, which would mean their velocities would be completely unknowable. Even at the coldest temperatures experimentally achieved in the lab, physicists still record a faint heat from the potential (but not quite actual) velocities of all the constituent particles inside an atom.

But we don’t have to restrict ourselves to atoms. Let’s do away with them altogether by creating a square-inch-sized vacuum with no particles at all. Surely there would be nothing inside?

Not according to physicist Paul Dirac. Among his several contributions to the field of physics was the early development of quantum field theory. After Einstein demonstrated that the aether does not exist, quantum field theory is the idea that eventually replaced it, though on first glance, the two concepts seem very similar.

The aether was conceived of as a physical substance through which energy propagated, in the same way that sound waves are created by sonic air compressions.

Unlike the aether, quantum field theory states that everything, both atoms and the space around them, is made of fields. For each elementary particle that we know of — electrons, quarks, neutrinos, etc. — there is a corresponding field that gives rise to them. The fields are considered to be quantum because they can only manifest themselves in discrete quantities, or quanta. The ground state for most of these fields is zero, which corresponds to a space with “no” particles (the notable exception being the Higgs field. If you want to know why, there’s fun sombrero visualization that helps explain it).

An absence of particles sounds promising! Even if the world is permeated with fields, perhaps those fields are perforated with emptiness. You probably know where this is going…

Quantum field theory has one last trick up its sleeves to subvert our expectations, and again, we have Heisenberg to thank for it. Not only can we not measure a particle’s momentum and position simultaneously, it turns out that time and energy also have a similarly inverted relationship. The more you know about how much energy a particle has, the less you know about how long the particle will remain in that energetic state. Again, this is not due to a limitation in scientific instruments but instead is an inherent property of matter and energy. This means the longer a particle remains in a particular state, the more precisely you can measure its energy.

Let’s look at our hydrogen atom again, which has one proton, one neutron, and one electron. Hydrogen is fairly stable, meaning it can stick around in the same form for a long time. That means you can pretty accurately measure the amount of energy stored in its subatomic particles.

For incredibly small time scales, on the order of a zeptosecond (10-21 seconds), the less certain you can be about how much energy a particle or a field or empty space contains. If you could zoom into a square inch of empty space fast enough, you’d see what you mistook for nothingness is actually a roiling sea of what physicists call “virtual particles.” These particles materialize from nowhere and exist for such an infinitesimally short amount of time that they can break the first law of thermodynamics — the one that says energy can neither be created nor destroyed — without anyone noticing. Nearly as soon as they arrive, virtual particles vanish back into the formless void.

We have to be careful here, however. Virtual particles aren’t real, in the sense that they don’t stick around and cannot be directly observed. In a way, they’re merely a mathematical tool to describe something for which we don’t seem to have an analogue up here in the macro world.

But whatever virtual particles are or are not, you and I observe them indirectly all the time. Virtual photons are the reason we have electricity in our homes and magnets on our fridge. Virtual gluons hold quarks together, which allows for the formation of atoms, molecules and planets. Virtual W and Z bosons spark the radioactive decay that powers our sun. An as-of-yet unknown virtual particle might mediate gravity.

In any case, it would seem that we’ve hit a wall. No matter where or how hard we look, we seem incapable of finding a discrete space that can be defined as something and another space that is devoid of that something. Instead, both seem to be polar but unified properties of a grand whole, which is us. Einstein put it this way, “We may therefore regard matter as being constituted by the regions of space in which the field is extremely intense… There is no place in this new kind of physics for both the field and matter, for the field is the only reality.”

At the subatomic scale where time no longer has any meaning we’re capable of comprehending, there is one additional property of matter that helps clarify what our universe of stuff is made of. It also creates the equally perplexing mystery of why we have a universe of stuff at all.

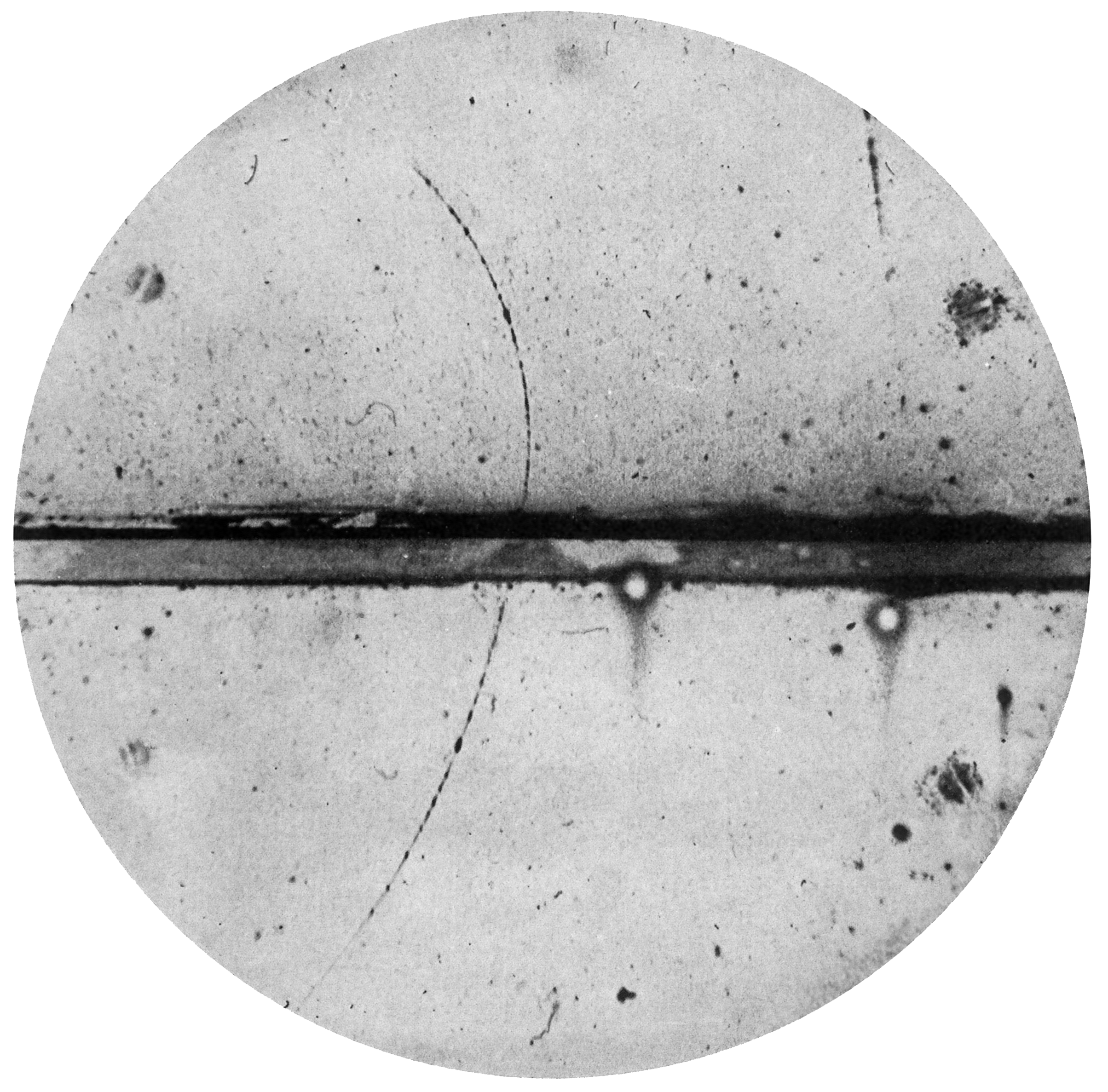

In the process of formulating the first iteration of quantum field theory, Paul Dirac hit a snag. Dirac was exclusively modeling electrons, and the math he’d derived beautifully and accurately described their behavior — but it would only do so if he presupposed the existence of an entirely new type of particle, one with the exact same properties (mass, spin) as an electron, but a positive rather than negative electric charge.

Instead of throwing out the math and starting from scratch, Dirac left the new type of matter in his equations. He concluded that the universe contained within it a type of matter that physicists had been totally unaware of up to that point. Four years later, positrons were indirectly observed in a bubble chamber, verifying his prediction. Scientists had discovered anti-matter.

We’ve learned a lot more about anti-particles since Dirac, and physicists have developed multiple mathematically equivalent ways of thinking about them. The physicist Richard Feynman, for example, thought of positrons as electrons that were moving backward through time.

We now know that every type of particle with mass and charge has a corresponding anti-particle and both are always created in equal amounts. Virtual particles with mass and charge, for example, always arise from the void in matter/anti-matter pairs. In fact, there theoretically should have been equal amounts of matter and anti-matter created in the first moments of the universe. If that had been the case, all of it would have combined and annihilated, leaving behind nothing but energy. Since we live in a universe of stuff, we can be confident this didn’t happen, but why is that the case?

We’ll answer that question in the next and final installment of this introductory series, in which a fictional girl with synesthesia and a real printmaker with a passion for Florida’s wild spaces help clarify exactly what anti-matter is and isn’t.